25 Jul 2010

I just returned to the US after eight months living in Taiwan. The trip was

great fun for me and my family. But more than that, it was a very productive

time for me to learn new programming technologies.

Why was my trip so productive?

I think some of the reasons were:

- I was away from my home computer set up (including video game consoles and a large TV). All I had was a Mac Mini (for the family to use), a MacBook Pro (for work) and a Nexus One phone.

- I commuted by bus rather than car. While my commute time was longer, it was much more productive. Instead of having to concentrate on driving, I had 40 minutes a day of free time to think, web surf, and even code.

- I didn’t follow local politics, and USA politics were made less interesting by distance and time zone. I stopped visiting political web sites and obsessing over current events.

- The timezone difference between Taipei and the US ment that email became a once-a-day event, rather than a continuous stream of interruptions.

- It’s more time-efficient to live as a guest in a city than as a home owner in the suburbs. For example, my mother-in-law cooked our meals, and I didn’t have nearly as many household chores as I do in America.

- Location-based internet blocks ment that some of my favorite time-wasting web sites (Pandora, Hulu) were unavailable.

- Having to explain and defend my technology opinions to my Google Taipei coworkers. “Go is a cool language” I would say. “Oh yeah? Why?” they would reply. I would struggle to explain, and usually both of us would end up more enlightened.

Beyond that, I think being in a new environment, and removed from my home,

helped shake me loose from my mental ruts. I was learning how to live in a new

physical environment, and that transfered over to how I used the web as well.

What did I do?

- I visited Hacker News frequently. It is a very good source of news on the startup business and new web technologies. Hacker News was where I first learned about Node.js and CoffeeScript, two of my current interests.

- I entered the Google AI Challenge, a month long Game AI programming contest. I didn’t place very high, but I had fun competing.

- I gave two talks on the Go programming language. One at the Google Taiwan office, the other at the Open Source Developer Conference Taiwan OSDC.tw. Having to give a talk about a programming language helps increase one’s understanding of that language.

- An afternoon spent hanging out with JavaScript Mahatma Douglas Crockford. I worked with Douglas ages ago when we both worked at Atari. It was great to catch up with him and his work. (He was in town to give a speech at the OSDC conference.)

- I joined GitHub, and started using it to host my new open source projects.

- I wrote Taipei-Torrent, a Bit Torrent client written in “Go”.

- I started summerTorrent, a Bit Torrent client written in JavaScript, based on node.js

- node.js - an interesting server-side JavaScript environment.

- CoffeeScript - a JavaScript preprocessor that looks like a promising language.

- PhoneGap - a cross-platform mobile JavaScript / HTML5 UI framework. I wrote a word scramble game using this framework.

- DD-WRT routers. I bought four new DLink 300 routers (which are dirt cheap), installed DD-WRT on them, and used them to upgrade my Taiwan relatives’ computer network.

- My nephew bought a PS3, so I finally had a chance to see Little Big Planet and Flower, two games I had long wanted to know more about. I also got to see a lot of Guitar Hero being played. Unfortunately I didn’t get a chance to actually play any of these games – someone else always had a higher claim on the TV.

Keeping the Taipei Experience Alive

I’m back in the US, and am already starting to slip back into my old ways.

Here are some ways I’m trying to keep my productivity up:

- Cool side projects.

- I’m going to continue to work on side projects to learn new things. I want to do something serious with CoffeeScript and Node.js.

- iPad. I’m getting one in a few weeks, and looking to see if its a useful paradigm.

- Get rid of distractions.

- I’m selling off (or just closeting) distractions like my older computers and my media center.

- I edited my /etc/hosts file to block access to all my top time-wasting web sites. Hopefully I won’t just replace these with a new generation of web sites.

- Working at home. My work office here in the US is just too noisy for me to concentrate in. I’m going to start spending as much time as possible working from a quiet room at home.

- Regular exercise. I got a lot of walking done in Taiwan. I’m going to take up running again. (Easy to do now, we’ll see how it goes when the weather gets rough.)

- I may even get a pair of “Gorilla Shoes” for barefoot running.

18 Jun 2010

The ICFP 2010 contest rules have been posted,

and I am quite disappointed by this year’s contest.

This year’s contest is difficult to describe. It’s too clever by half, and it

depends too much on time, and too much on repeated interaction with the

organizer’s servers.

The conceit is that you’re designing “car engines”, and “fuel for car

engines”. A car engine is a directed graph with certain properties, and “fuel”

is a directed graph with other properties that generates a set of coefficients

that are fed to the engine.

Layered on top of that is an encoding puzzle (you have to figure out how the

engine and fuel directed graphs are encoded for submission to the IFCP

servers.)

Layered on top of that is an economy where you are encouraged to submit your

own car engines and write optimal fuels for other people’s car engines. There

are benefits for finding better fuels for existing car designs. (You aren’t

provided the details of the other car designs.)

Layered on top of that is that the instructions are not written very clearly.

I had to read them multiple times to start to even begin to understand what

was going on.

And finally, the contest registration / submission web site is returning 503

(Service Temporarily Unavailable) errors, either because it hasn’t been turned

on yet, or perhaps because hundreds of teams are trying to use it at once.

I suspect this contest is going to be difficult for teams with limited

Internet connectivity. I also suspect the contest servers are going to be very

busy later in the contest as people start hitting them with automated tools

repeatedly in order to start decoding engines.

I salute the contest organizers for trying to get contestants to interact with

each other during the contest, and for coming up with an original idea.

I fault them for designing a “write your program in our language, not yours”

puzzle. I want to enjoy programming in the language of my choice, not design

graphs and finite state automata for creating fuel coefficients and engines.

I am going to punt this year – the contest just doesn’t sound very fun.

I hope next year’s topic is more to my taste!

08 May 2010

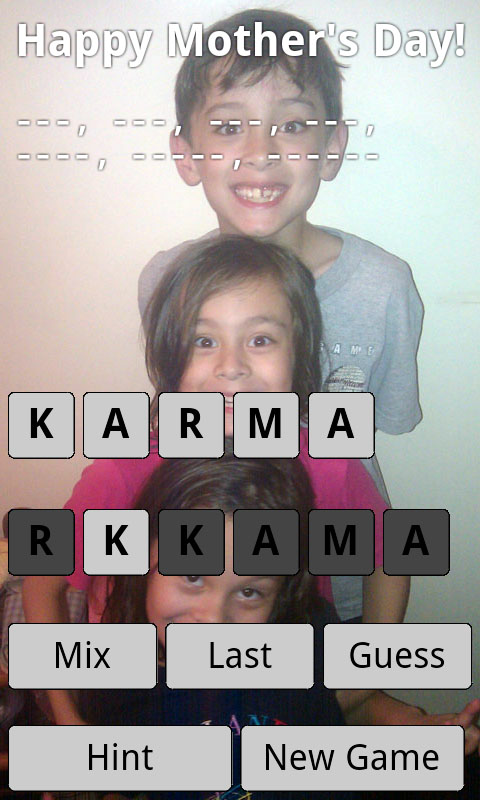

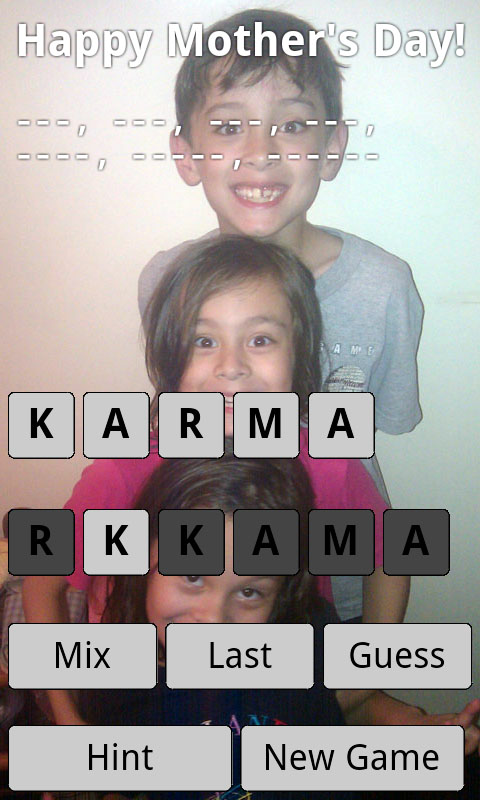

Happy Mother’s Day everyone! This year I wrote an Android app for my wife for

Mother’s Day. How geeky is that?

Happy Mother’s Day everyone! This year I wrote an Android app for my wife for

Mother’s Day. How geeky is that?

The reason I wrote it is that my wife’s favorite Android application, Word Mix

Lite, recently added annoying banner ads. While the sensible thing to do might

have been to switch to another app, or perhaps upgrade to the paid version of

Word Mix, I thought it might be interesting to see if I could write my own

replacement.

And as long as I was writing the app, I though I’d try writing it using

JavaScript. Normally Android applications are written in Java, but it’s also

possible to write them in JavaScript, by using a shell application such as

PhoneGap.

Why use JavaScript instead of Java? Well, hack value mostly. On the plus side

it’s a fun to write! Another potential plus is that it is theoretically

possible to run the same PhoneGap application on both Android and Apple.

The drawback is that PhoneGap is not very popular yet, especially among

Android developers, and so there is relatively little documentation. I ran

into problems related to touch events and click events that I still haven’t

completely solved.

It took about three days to write the application. The first day was spent:

- Finding a public domain word list.

- Filtering the word list to just 3-to-6 character words.

- Build a “trie” to make it fast to look up anagrams.

- Output the trie as a JSON data structure.

The second day was spent writing the core of the word jumble game.

- This was all done on a desktop, using Chrome’s built-in Javascript IDE.

The third day was spent:

- Porting to PhoneGap.

- Debugging Android-specific issues.

- Tuning the gameplay for the phone.

The project went pretty well.

- JavaScript is a very easy language to work in.

- CSS styling was fairly easy to learn.

- Targeting a single browser made it relatively easy to use the DOM.

- The Chrome JavaScript debugger was very helpful.

- The web has a wealth of information on JavaScript and HTML / CSS programming information.

In the end there were unfortunately a few button-event UI glitches I couldn’t

solve in time for Mother’s Day. When I get some spare time I’d like to revisit

this project and see if I could use the JQTouch

library to solve my UI glitches. I’d also like to make an open source release

of a reskinned (non-Mother’s Day themed) version of this app. And then who

knows? Maybe I’ll release it for the other phones that PhoneGap supports as

well. :-)

06 Mar 2010

Team Blue Iris

(that’s me!) placed 77th out of 708 in the

Google AI Challenge 2010 contest. The contest was to design

an AI for a Tron lightcycle game.

My entry used the standard min/max approach, similar to many other entries. I

guess that’s why it performed similarly to so many other entries. :-) I didn’t

have any time to investigate better algorithms, due to other obligations.

In addition to my own entry (which was in C++), I also created starter packs

for JavaScript and Google’s Go language. These starter packs enabled people to

enter the contest using JavaScript or Go. In the end,

6 people entered using Go, and

4 people entered using JavaScript.

I’m pleased to have helped people compete using these languages.

I initially wanted to use JavaScript and/or Go myself, but the strict time

limit of the contest strongly favored the fastest language, and that made me

choose a C++ implementation. Practically speaking, there wasn’t much advantage

to using another language. The problem didn’t require any complicated data

structures, closures, or dynamic memory allocation. And the submitted entries

were run on a single-hardware-thread virtual machine, which meant that there

wasn’t a performance benefit for using threads.

This contest was interesting because it went on for a long time (about a

month) and because the contestants freely shared algorithm advice during the

contest. This lead to steadily improving opponents. My program peaked at about

20th place early in the contest, but because I didn’t improve it thereafter,

its rank gradually declined over the rest of the contest.

The contest winner’s post-mortem

reveals that he won by diligent trial-and-error in creating a superior evaluation function. Good

job a1k0n!

Congratulations to the contest organizers for running an interesting contest

very well. I look forward to seeing new contests from the University of

Waterloo Computer Club in the future.

23 Jan 2010

I wanted to learn more about how the original BitTorrent client implemented

“choking”, so I downloaded the source to the original Python-based BitTorrent

client from SourceForge.

I was impressed, as always, by the brevity and clarity of Python. The original

BitTorrent client sources are very easy to read. (Especially now that I

understand the problem domain pretty well.) The code has a nice OO design,

with a clear separation of responsibilities.

I was also impressed by the extensive use of unit tests. About half the code

in the BitTorrent source is unit tests of the different classes, to make sure

that the program behaves correctly. This is a really good idea when developing

a peer-to-peer application. The synthetic tests let you test things like your

end-of-torrent logic immediately, rather than by having to find an active

torrent swarm and wait for a real-world torrent to complete.

When I get a chance I’m going to refactor the Taipei-Torrent code into smaller

classes and add unit tests like the original BitTorrent client implementation

has.

And come to think of it, why didn’t I check out the original BitTorrent client

code sooner? It would have saved me some time and I’d probably have a better

result. D’Oh! Oh well, live and learn!

23 Jan 2010

From Scientific American:

Binary Body Double: Microsoft Reveals the Science Behind Project Natal

Short summary: They used machine-learning algorithms and lots of training data

to come up with an algorithm that converts moving images into moving joint

skeletons.

Given the huge variation in human body shapes and clothing, it will be

interesting to see how well this performs in practice.

I bet people will have a lot of fun aiming the Natal camera at random moving

object to see what happens. I can already imagine the split-screen YouTube

videos we’ll see of Natal recognizing pets, prerecorded videos of people,

puppets and marionettes.

Oh, and of course, people will point Natal back at the TV screen and see if

the video game character can control itself.

Great fun!

22 Jan 2010

Wow, my Taipei-Torrent post made it to Hacker News and

reddit.com/r/programming. I’m thrilled!

One comment on Hacker News was “800 lines for a bencode serializer?! It only

took me 50 lines of Smalltalk!” That was a good comment! I replied:

A go bencode serialization library could be smaller if it just serialized

the bencode data to and from a generic dictionary container. I think another

go BitTorrent client, gobit, takes this approach.

But it’s convenient to be able to serialize arbitrary application types.

That makes the bencode library larger because of the need to use go’s

reflection APIs to analyze and access the application types. Go’s reflection

APIs are pretty verbose, which is why the line count is so high.

To make things even more complicated, the BitTorrent protocol has a funny

“compute-the-sha1-of-the-info-dictionary” requirement that forces BitTorrent

clients to parse that particular part of the BitTorrent protocol using a

generic parser.

So in the end, the go bencode serializer supports both a generic dictionary

parser and an application type parser, which makes it even larger.

In general, Taipei-Torrent was not written to minimize lines-of-code. (If

anything, I was trying to maximize functionality per unit of coding time.) One

example of not minimizing lines-of-code is that I used a verbose error

handling idiom:

a, err := f()

if err != nil {

return

}

There are alternative ways to handle errors in go. Some of the alternatives

take fewer lines of code in some situations. The above idiom is my preference

because it works correctly in all cases. But it has the drawback of adding 3

lines of code to every function call that might return an error.

The go authors are considering adding exceptions to the go language. If they

do so it will probably dramatically improve the line count of Taipei-Torrent.

20 Jan 2010

This is a BitTorrent client. There are many like it, but this one is mine.

-- the BitTorrent Implementer’s Creed

For fun I’ve started writing a command-line BitTorrent client in Google’s go

programming language. The program, Taipei-Torrent ,

is about 70% done. It can successfully download a torrent,

but there are still lots of edge cases to implement.

Go routines and channels are a good base for writing multithreaded network

code. My design uses goroutines as follows:

- a single main goroutine contains most of the BitTorrent client logic.

- each BitTorrent peer is serviced by two goroutines: one to read data from the peer, the other to write data to the peer.

- a goroutine is used to communicate with the tracker

- some “time.Tick” goroutines are used to wake the main goroutine up periodically to perform housekeeping duties.

All the complicated data structures are owned by the main goroutine. The other

goroutines just perform potentially blocking network I/O using channels,

network connections, and []byte slices. For example, here’s a slightly

simplified version of the goroutine that handles writing messages to a peer:

func (p *peerState) peerWriter(errorChan chan peerMessage,

header []byte) {

_, err := p.conn.Write(header)

if err != nil {

goto exit

}

for msg := range p.writeChan {

err = writeNBOUint32(p.conn, uint32(len(msg)))

if err != nil {

goto exit

}

_, err = p.conn.Write(msg)

if err != nil {

goto exit

}

}

exit:

errorChan <- peerMessage{p, nil}

}

Good things about the Go language and standard packages for this project:

- Even without IDE support it is easy to refactor go code. This ease-of-refactoring makes it pleasant to develop a program incrementally.

- Goroutines and channels make networking code easy to write.

- The log.Stderr() function makes debugging-by-printf fairly painless.

- Go maps serve as pretty good one-size-fits-all collection classes.

- I received very fast responses from the go authors to my bug reports.

- The standard go packages are reliable and easy to use. I used the xml, io, http, and net packages pretty extensively in this project. I also used the source of the json package as a base for the bencode package.

- gofmt -w is a great way to keep my code formatted.

- Named return values, that are initialized to zero, are very pleasant to use.

- The code writing process was very smooth and stress free. I rarely had to stop and think about how to achieve what I wanted to do next. And I could often add the next feature with relatively little typing. The feeling was similar to how it feels when I write Python code, only with fewer type errors. :-)

- With the exception of using the reflect package I never felt like I was fighting the language or the compiler.

Minor Problems:

- It was a little tedious to write if err != nil {return} after every function call in order to handle errors.

- The standard go http package is immature. It is missing some features required for real-world scenarios, especially in the client-side classes. In my case I needed to expose an internal func and modify the way a second internal func worked in order to implement a client for the UPnP protocol. The good news is that the http package is open source, and it was possible to copy and fork the http package to create my own version.

What wasted my time:

- Several hours wasted debugging why deserializing into a copy of a variable (rather than a pointer to the original variable) had no effect on the value of the original variable. I notice that I often make mistakes like this in go, because go hides the difference between a pointer and a value more than C does. And there’re confusing differences in behavior between a struct (which you can pass by either value or reference) and an interface (which has reference semantics on its contents even though you pass the interface by value). When you are reading and reasoning about go code you must mentally keep track of whether a given type is a struct type or an interface type in order to know how it behaves.

- Several hours wasted figuring out how to send and receive multicast UDP messages. This may be an OSX-specific bug, and it may already be fixed. I found the Wireshark packet sniffer very helpful in debugging this problem.

- Several hours wasted with crashes and hangs related to running out of OS threads on OSX. This was due to my code instantiating time.Tick objects too frequently. (Each live time.Tick object consumes a hardware thread.)

- Many hours spent trying to understand and use the reflect package. It is powerful, but subtle and mostly undocumented. Even now, some things remain a mystery to me, such as how to convert a []interface{} to an interface{} using reflection.

Project statistics:

- Line count: Main program: 1500 lines, http package patches: 50 lines, UPnP support: 300 lines, bencode serialization package: 800 lines. Tests for bencode serialization: 300 lines

- Executable size: 1.5 MB. Why so large? One reason is that go doesn’t use shared libraries, so everything is linked into one executable. Even so, 1.5 MB seems pretty large. Maybe go’s linker doesn’t strip unused code.

- Development time: ~8 days so far, probably 11 days total.

- The source is available under a BSD-style license at: github.com/jackpal/Taipei-Torrent

Edits since first post:

- Added error reporting to code example.

- Added a link to the source code.

- Give more details about the line count. I had mistakenly included some test code in the lines-of-code for the main program.

- Add a statistic about program size.

18 Jan 2010

An excellent little performance optimization presentation that shows how

important memory layout is for today’s processors:

Pitfalls of Object Oriented Programming

The beginning of the talk makes the observation that since C++ was started in

1979 the cost of accessing uncached main memory has ballooned from 1 cycle to

400 cycles.

The bulk of the presentation shows the optimization of a graphics hierarchy

library, where switching from a traditional OO design to a structure-of-arrays

design makes the code run 3 times faster. (Because of better cache access

patterns.)

18 Dec 2009

I just noticed Tom Forsyth, aka tomf, is speaking at the

Stanford EE CS Colloquium on January 6, 2010. The

video will hopefully be posted on the web afterwards.

The topic is “To be announced”, but is very likely to be Larrabee related.

Happy Mother’s Day everyone! This year I wrote an Android app for my wife for

Mother’s Day. How geeky is that?

Happy Mother’s Day everyone! This year I wrote an Android app for my wife for

Mother’s Day. How geeky is that?